Yoo La Shin Solo Exhibition: White Velvet

-Opening : 6pm, Sep 8th(Fri), 2017

-Organized by: Alternative Space LOOP

Yoo La Shin Solo Exhibition: White Velvet

-Opening : 6pm, Sep 8th(Fri), 2017

-Organized by: Alternative Space LOOP

신유라 개인전: 화이트 벨벳

-오프닝 : 2017년 9월 08일(금) 오후 6시

-주최/주관: 대안공간 루프

Years of experience have taught us to take ordinary life and the familiarity of our day-to-day routines for granted. We label the things we see every day as ‘unremarkable’, never to perceive them as anything more than what they seem to be on the surface. The convenience and comfort that comes with familiarity make it difficult for us to question and reflect on the way we look at the world. Although some claim that the advent of pluralism has changed the way people see things, complacence in familiarity still keeps us enslaved to the dominant social framework, which tries to maintain uniformity by dragging the individual into the logic of the whole. The price of settling for the dominant framework is submission to the controlling mechanisms of society. However, many people are compelled to pay that price voluntarily because they want to be part of the whole—and because they fear the exclusion that results from breaking away from the whole. Thus the dominant framework becomes internalized in our thought processes.

But Yoo La Shin, discomforted by the rules and control that the dominant framework demands, creates unnatural, illogical situations that would induce dissonance and discomfort in the current status quo, forcing us to question what we thought to be incontrovertible truths. With her earlier objets d’art, Yoo La Shin wove together familiar objects in unfamiliar ways. In order to force us to question the order and meanings we assigned to the familiar items that composed the objets, she created discomforting and undefinable landscapes, confronting us with a sense of semantic dissonance and incongruity. Thus, Shin allowed us to rediscover experiences and values we had numbed ourselves to because they were so ordinary. Shin’s recent work is an extension of her earlier reexamination of the mundane. She brings together completely antithetical concepts and situations to create confusing paradoxes, and compels us to reverse the hierarchy of our internalized semantic framework. The act of reversal exposes the complexity and irrationality of our pluralistic reality, which cannot be fully comprehended with traditional frameworks of understanding. Not only that, the reversal elevates us to a new, hidden level of understanding concealed in the foundations of phenomenological semantics. Her paradoxes may go against what we consider common sense and wear the skin of self-contradiction and irrationality, but they point to truths that are often difficult to capture.

The pieces in this exhibition cast binary opposites as equals, creating paradoxes composed of conflicting elements like exposure and concealment, present and past, peace and violence, spiritualism and materialism, beauty and hatred, and grand ideology and unremarkable daily life. By perceiving and examining the meanings of both opposing elements at once amidst the tension created by the collision and conflict between them, we may discover new perspectives on issues that are often easy to overlook. Shin’s work in this exhibition also differs from her previous work in terms of formal composition. Rather than reorganizing and assembling found objects as she did in the past, she took the time to personally craft many of the items used in her work. The decorative and aesthetic nature of the pieces is highlighted by the lightweight and fragile materials that compose the objects. However, the content of her work is anything but lighthearted. She discusses heavy topics such as hierarchical values, historical perception, otherness, and the imbalance between materialism and spiritualism.

The contrast between form and content in Shin’s work is also a paradox in and of itself. These works of hybrid art seem nonsensical at first glance because they do not conform to our traditional frameworks of understanding. But—in a reflection of the complexity of relationships in society—under the camouflage, what seems alien at first turns out to be something very familiar indeed.

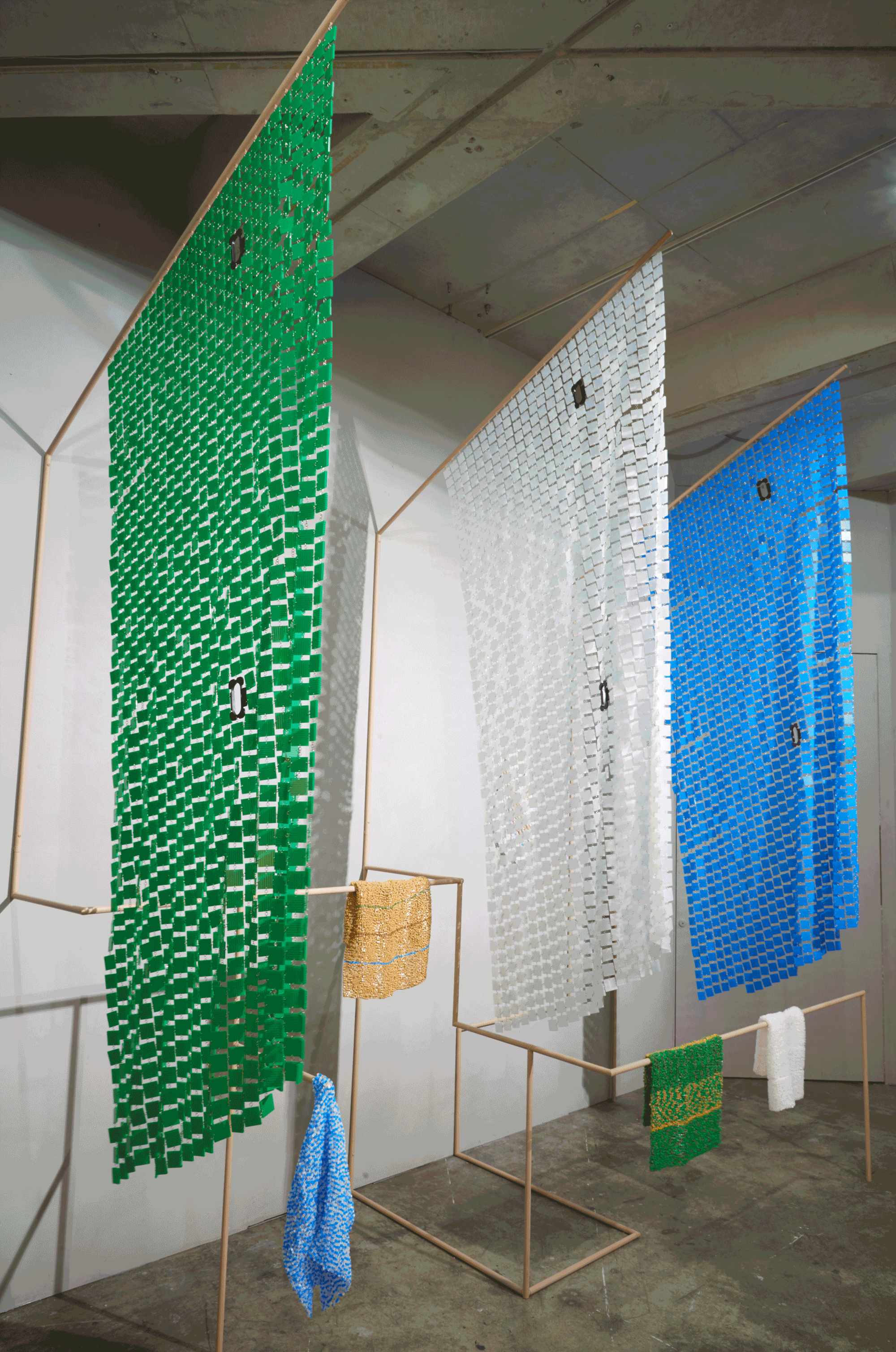

is made of the familiar plastic evidence boxes used by prosecutors whenever news of corruption surfaces in the media. The boxes have been cut into small rectangular modules and woven with different fabrics. Some of the fabrics are ordinary towels and others are massive flags of blue, green, and white—colors representing the flag of the prosecutor’s office. Though both flags and towels are made of fabric, they could not be any more different. A flag is a dignified, almost totemic symbol of an organization and speaks for the status of the organization it represents. The semantic weight of the flag seems to give it a superior status to towels, which have no special significance in the world save for their specific utility. However, Shin questions the statuses assigned to what these two fabrics represent. The weight of political power is represented by the flags, which stand for the prosecutors whose ivory towers were built upon the foundations of hypocrisy and falsehood. The ordinary people and their lives are represented by the simple towel, which is humble but true to its duty. By juxtaposing these elements, Shin forces viewers to reexamine the hierarchies they have internalized.

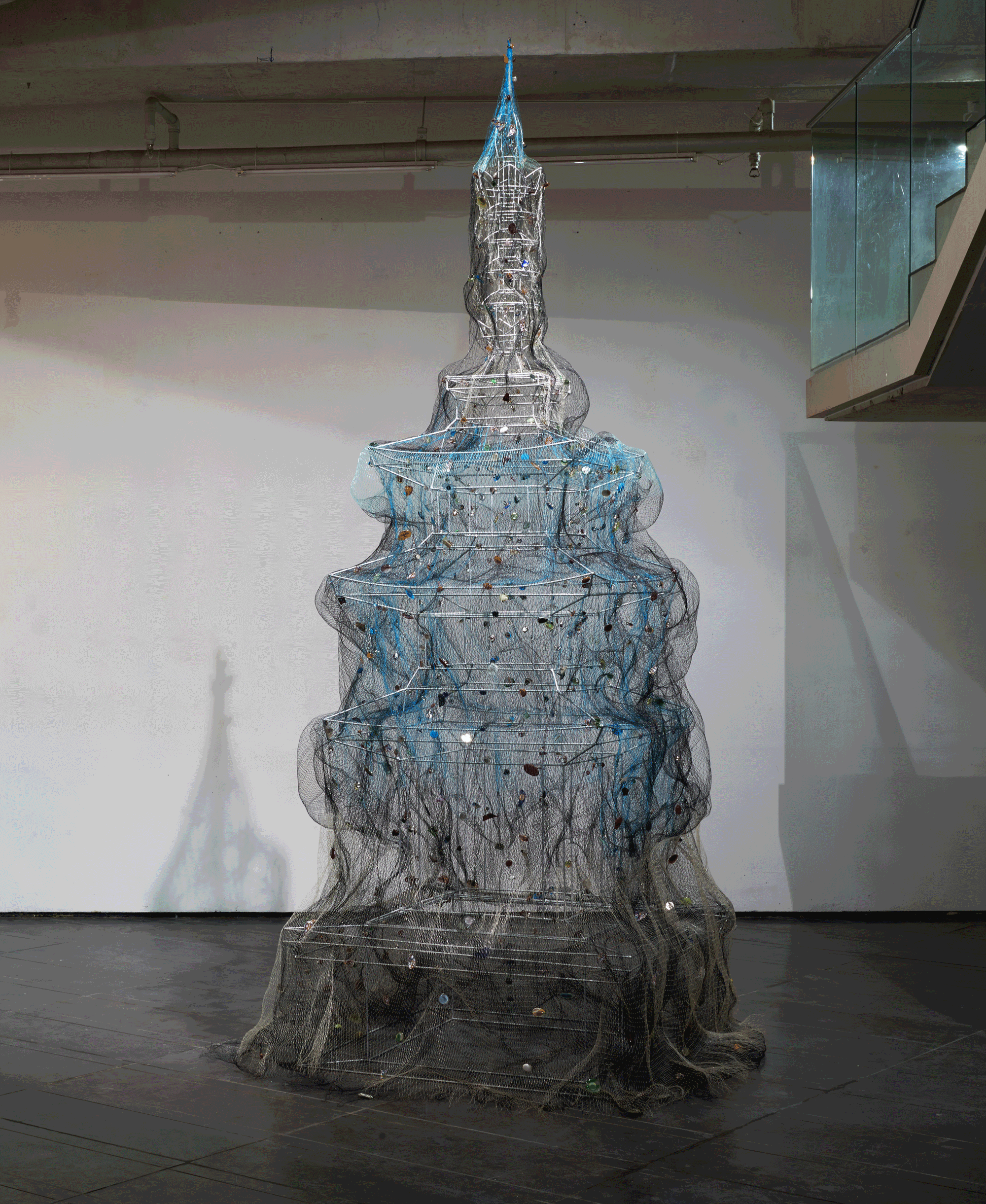

Is another combination of binary opposites—this time of spirituality and materialism. Accessories made from Venetian glass shards hang from a net draped over a scaled frame-replica pagoda, which is a religious symbol representing spiritual value and the sublime. It is no exaggeration to say that no matter the time or place, everything we do is surrounded by the all-encompassing net of capitalism. Even religion—the ultimate spiritual value system—is not immune from subordination by the economic and material values brought in by capitalism. Pagodas were originally built to remind people of the spiritual heights reached by Buddha and to help them engrave his teachings into their hearts. But over time, their purpose became warped into a wish-fulfillment vehicle for our desires. In this work, the spiritual value of religion continues to resonate from inside the hollow interior of the lonely pagoda caught in a net of extravagant jewelry. With this contrast, Shin creates a metaphor for the perilous state of religion and spirituality, which is being encroached upon by worldly materialism.

Yoo La Shin’s work evokes humor by subverting our expectations, creating a disconnect between things we instinctively perceive as ordinary and the meanings hidden beneath them. It can also be considered satire in that it maintains a critical stance on social conditions and social pathology. And though her work induces dark and unfamiliar feelings of fear, it is far from pessimistic or self-absorbed. Shin expresses herself in ways that acknowledge all sides and in ways that are morally ambiguous and multi-layered, and demands that those who engage with her work take up multiple perspectives and actively participate in trying to decipher its meanings.

Shin’s light art, is composed two main elements. The first is lighting fixtures such as chandeliers—whose beautiful form and decadence have made them a symbol of wealth and grandeur. However, placed under the lights is the second element—repulsive objects such as rotten teeth, a rat and a mousetrap, and unnamed insects. The contrast struck when the lights cast their beautiful glow on the lowly and grotesque items below create a paradoxical landscape. Shin’s rebellious imagination dares to shed light on the dark places inhabited by things our civilization—out of a desire to maintain peace and harmony—tries to hide and eliminate. And by doing so, she grants equal standing to the things that had been part of ourselves but othered and oppressed and rejected. She acknowledges the characteristics that make these othered things different while attempting to restore our relationships with them.

is a beautiful, elegant veil cast across part of the exhibition space. It lures in viewers with its splendor and implied secrets. But it dashes those expectations, drawing our gazes to the images on its surface—images of gruesome genocide and oppressive violence. The contrast between the beauty of the veil and the dark imagery evokes a sudden, disturbing sense of psychological dissonance. It is reminiscent of the way uncomfortable historical truths, which exist no matter how much we try to look away from them, are part of the veil that composes the peaceful and comfortable reality we inhabit today. Though the hidden truths make reality more valuable, we often overlook them. Only when we take a short detour around the alluring veil and reexamine it do we see the horrifying images on its surface. This curtain, an intricate combination of the opposing elements of exposure (beautiful ornamentation, the peaceful present day) and concealment (the gruesome imagery of genocide, dark history), is a mechanism that forces us to reflect on our epistemological attitudes towards history. History is something we cannot fully comprehend through a superficial reading. Veil I suggests a change in perspective, calling on us to look deeper than the surface. At the same time, it captures the idea that the discomforting images that compose the curtain are real, historical facts that must not be overlooked.

The works of Yoo La Shin are undeniably subversive. They reject and defy faith in the dominant framework that is (supposedly) universally valid and is the crux of the world we live in. Her subversions create cracks in the firm beliefs and thought processes instilled within us, compelling us to develop an awareness of and a response to these once-incontrovertible ideas. This self-reflection will lead us closer to the realities ignored by individuals and society, and to the othered people whom we have rejected and attempted to expel, among other essential and material truths. If that is the case, then perhaps subversion is not such a bad thing after all.

Written by Jungah Lee

Curator, Alternative Space LOOP

전혀 특별할 것 없는 반복되는 일상적 삶과 그 속에서 마주하는 익숙한 현상과 사물은 오랜 기간 동안 이어져 온 경험과 학습에 의해 너무나 명백한 것이라 믿기 때문에 그저 표면적 인식의 영역에 무미건조하게 머물기 쉽다. 그러나 익숙함에서 오는 편리함과 안도감으로 인해 그러한 관성화된 습관과 믿음은 의심하고 거스르기엔 너무나 견고한 것도 사실이다. 이는 우리가 다원화된 시대를 맞아 새로운 인식의 장을 맞았다고는 하지만 개인을 전체의 논리 안으로 포섭하여 사회를 균일하고 단일한 질서로 유지하려는 지배 논리가 여전히 유효하게 작동하는 기제가 될 수 있다. 보편적 질서의 프레임 안에 안주하는 대가는 아이러니하게도 전체와의 동일화 욕망과 동시에 이탈에 따른 배제의 두려움으로 인해 통제 장치에 자발적으로 동의하고 순응하는 것이다. 이렇게 내면화되는 지배 논리가 줄곧 요구하는 규율과 통제가 불편하게 다가온 신유라는 아무런 의심 없이 당연한 것으로 여기는 고착화된 인식의 틀 안에서 오히려 낯설고 불편을 느낄 작위적이고 비논리적인 상황을 연출하여 보는 이로 하여금 혼란에 빠지게 한다.

일상에서 수집한 사물들을 보편 상식으로는 연결시키지 못할 이질적인 조합으로 구성했던 신유라의 이전 오브제 작업은 ‘인지의 불균형’과 ‘의미의 비일관성’으로 빚어내는 불편하고도 모호한 풍경을 통하여 익숙하고 흔한 사물들의 질서와 의미작용에 의문을 던짐으로써 고정되고 관습화된 우리의 현실 인식 태도를 되돌아보게 하였다. 이러한 이전 작업이 사소한 사물들 간의 비정상적이고 왜곡된 관계에서 생겨난 수많은 틈새로 보편적 가치와 일상적 현상을 인식하는 방식에 대한 새로운 시각을 투사하거나 우리가 그간 일상적 범주에 안주하며 외면하거나 무감각했던 경험과 가치들을 재발견하도록 했다면 최근의 작업은 그 연장선상에서 더 나아가 좀처럼 양립할 수 없는 두 개의 상반된 개념이나 상황, 그러한 상충하는 요소들이 공존하면서 일으키는 역설을 의도적으로 조장하여 사물 간 의미체계의 교란과 전복을 더욱 극단으로 치닫게 함으로써 정합적 논리로 이해할 수 없는 다원적 현실의 복잡성과 부조리를 환기시킬 뿐만 아니라 현상적 의미작용 기저에 숨겨진 다른 차원의 이해로 다가서게 한다. 이번 전시의 신작들을 보면 드러남과 감춤, 현재와 과거, 평화와 폭력, 정신성과 물질주의, 미와 혐오, 거대 이념과 평범한 일상성 등 상반되고 어긋나는 두 요소들이 대등하게 양립하여 모순적 대치상황이 활성화되고 있는데 이 때 대립하는 두 요소의 충돌과 갈등으로 유발되는 긴장의 구도 속에서 양 측면의 의미를 동시에 인식하고 살핌으로써 우리가 간과하기 쉬운 문제들을 새롭게 대면하게 된다.

본 전시의 작품들은 형식적인 면에서도 수집된 오브제를 재조합하여 배치하기보다 상당 부분 장기간에 걸쳐 수공으로 오브제 형상을 제작한 점에서도 변화를 보인다. 가볍거나 부서지기 쉬운 취약한 재료로 제작하고 장식성과 심미성이 더욱 두드러져 보이나 내용적으로는 위계적 가치관, 역사 인식, 타자성, 물질주의와 정신성의 불균형 등 상대적으로 꽤나 묵직한 주제들을 담지하고 있어 형식과 내용의 관계 또한 역설적으로 설정되어 있다. 역설은 외견상 상식에 반하고 자기모순과 부조리의 외피를 두르고 있지만 실상 진리를 지향하고 있다. 다만 그것을 쉽게 포착하지 못할 뿐이다. 신유라의 역설은 현대 사회의 복잡하고 혼란스러운 면면을 통찰하고 단적으로 제시하는 데 유용해 보인다. 다시 말해, 우리를 둘러싼 현실 자체가 일반 논리와 상식으로는 모든 진리에 도달할 수 없고 온전히 해독할 수 없는 현상과 문제들로 점철되어 있기에 작가가 도입한 모순어법은 그러한 부조리한 현실의 존재양식을 있는 그대로 담아내는 데 적합하다는 것이다. 한편으로는 합리적인 추론이나 인과관계를 무화시키고 정형화되고 확정적인 사유 방식에서 이탈된 이 전도된 설정이 조화나 완결을 유보시키도록 고안된 무대가 되어 작품에 숨겨진 궁극적인 의미와 본질적인 것을 탐색하는 새로운 경로를 제시하기도 한다.

이러한 혼성적 작업은 인식체계에 존재하지 않았던 것이기에 비현실적이고 허구적인 것으로 보일 수 있지만 위장 장막을 걷어내고 속내를 들여다보면 그 낯선 것은 결국 우리가 잘 알고 있던 것이고 우리가 딛고 있는 사회의 다층적인 관계를 반영하고 있다는 것을 알게 된다. ‹걸쳐진 상자›는 언론 매체를 통해 권력형 비리를 고발하는 보도나 기사를 접할 때면 예외 없이 등장하는 검찰 압수수색용 플라스틱 박스를 가로, 세로 3.5cm와 1cm 미만의 사각 모듈로 잘라 검찰청의 CI가 새겨진 깃발의 주조색인 청색과 녹색, 흰색의 거대한 깃발과 일상에서 흔히 사용하는 수건으로 손수 직물을 직조하듯 만들어 병치시켜 놓은 작업이다. 깃발은 일반적으로 개인 혹은 가문, 국가나 단체, 조직 등의 권위와 정체성, 전통이 집약되어 있으며 집단의 구심점이 되어 주는 상징물인데 특히, 우리나라 검찰청의 깃발은 아이러니하게도 권력층의 비리와 부패라는 부정적인 사건이 벌어질 때라야 종종 접하게 된다. 같은 직물이라도 깃발과 수건이 담고 있는 형이상학적 무게감은 확연한 차이를 갖는다. 집단의 위상과 명예를 표상하는 숭고하고 존엄한 표식 혹은 (최근의 일련의 집단 시위에서처럼) 신성시하여 토템적 의미로까지 작용하는 깃발의 상징적 혹은 정서적 무게감은 일상에서 특정한 용도 이외에 별다른 의미 부여를 하지 않는 사소한 수건의 그것과 비교한다면 훨씬 우월한 위치를 차지하는 듯 보인다. 그러나 신유라 작가는 온갖 위선과 허위로 키운 권력의 묵직함과 묵묵히 제 기능에 충실한 수건의 일상성과 평범함 사이에 존재하는 경중에 의문을 제기하며 그 위계적 관계에 대해 재고하게 한다.

정신성과 물질주의라는 또 다른 이항대립적 요소를 결합시킨 은 정신적 가치, 숭고함을 표상하는 종교적 상징물인 석가탑의 형상에 그물을 씌워 그 위에 베니스에서 수집한 유리 부산물로 만든 액세서리들을 매단 작업이다. 현 시대는 언제 어디서 무엇을 하든 촘촘한 망처럼 구축되어 있는 자본주의 논리에 포위되어 있다 해도 과언이 아닐 것이다. 자본주의가 부추기지만 결코 충족될 수 없는 욕망이 가져다주는 좌절감과 박탈감은 그 무엇으로도 보상받기 힘들며 절대적이고 궁극적인 정신적 가치체계인 종교마저 자본주의가 가져온 경제적, 물질적 가치에 예속되기 쉽다. 원래 부처의 사리를 모신 불탑은 부처의 열반의 의미와 그 분의 정신적 고매함을 기억하며 가르침을 새기게 하기 위해 세워진 조형물이었으나 언젠가부터 개인의 욕망을 채우기 위한 주술적 도구로 변질되어 왔다. 신유라는 여기서 온갖 화려한 장신구 망에 포위된 채 본체 없이 처량하게 서 있는 탑의 텅 빈 내부void에서 덧없이 공명하는 (종교의) 정신적 가치를 비유적으로 보여주며 세속적 물질주의에 잠식되어 온 종교의 세태와 정신성이 처한 시대적 위상에 대해 이야기하고 있다.

신유라의 작품들은 이와 같이 직관적으로 인지 가능한 드러난 것과 그 이면에 감추어진 의미 간 괴리로부터 기대와 예상을 어긋나게 함으로써 유머를 생성시키기도 하고 세태와 사회병리에 대한 비평적 시선을 견지한다는 점에서 풍자를 담지하기도 한다. 다른 한편으로는 음울하고 낯선 두려움을 유발하기도 하지만 비관적이거나 자폐적인 풍경과는 거리가 멀다. 그 표현 방식이 양가적이고 모호하며 중층적이기에 관람자에게 복수의 시선으로 더욱 적극적인 의미 해독에 가담해 줄 것을 요청하기 때문이다.

‹수집된 빛›, 일명 조명 작업들은 아름다운 조형성과 화려한 빛 덕분에 부와 격조의 상징물이 된 샹들리에를 비롯한 은은한 조명 기구에 발치된 썩은 치아, 쥐와 쥐덫, 이름 모를 날벌레와 같은 혐오스럽고 불쾌하거나 성가시고 하찮은 대상을 주요 재료로 사용함으로써 비천하고 추하며 그로테스크한 형상들이 불빛 속에서 더 매혹적으로 조명 받는 역설적 풍경을 만들어 낸다. 이러한 혐오스러운 대상들은 욱신거리는 통증이나 어둡고 음습한 서식지의 퀴퀴하고 눅눅한 냄새, 귓전에서 앵앵거리며 성가시게 하는 소리 등 우리의 다양한 감각과 긴밀하게 관계하면서 더 예민한 반응을 유발시키는지 모른다. 우리의 문명, 우리 사회가 안녕과 조화를 유지하기 위해 감추고 제거하고 싶어 하는 비천한 존재들의 거주지인 어두운 세계를 굳이 비추고자 하는 신유라의 이 불온한 상상은 우리 안의 일부였을 타자화되어 배척되고 억눌려 온 것들을 완전히 분리시키지 않고 오히려 대등한 지위를 부여함으로써 그들의 차이를 있는 그대로 인정하고 그들과의 관계 회복을 시도하는 것이다. 하나의 신념이나 가치관에서 벗어나 있는 또 다른 입장-타자-을 자기 진영으로, 또 자기 식대로 포섭하는 것은 갈등과 충돌의 봉합일진 모르나 또 다른 전체주의적 폭력에 지나지 않는다.

전시장 공간의 일정 부분을 가로지르며 장엄하게 드리워진 작품‹하얀 장막 Ⅰ›은 거대한 흰색 벨벳 커튼으로 이루어져 화사하고 우아한 분위기를 선사한다. 그리스 신화의 파라시오스가 벽에 그린 베일 그림에 속아 베일 뒤편에 무엇이 그려져 있는지 궁금해 했던 제욱시스의 일화처럼 베일은 종종 그 뒤편의 감추어진 실체를 전제한다. 신유라의 커튼 또한 그 후면의 존재를 추적하거나 그것이 공간에 부여하는 물성과 감각을 경험하고자 하는 관객의 기대를 이내 저버린다. 이 매혹적인 커튼은 관람자로 하여금 그 주위를 유영하다 문득 표면에 새겨진 그림에 눈을 돌리게 되면 잔혹한 대량 학살과 폭력(탄압)의 처참한 모습이라는, 외관과는 상반된 장면과 맞닥뜨리게 하여 순식간에 심리적 반전 상황에 놓이게 한다. 진실은 가장 눈에 잘 띄는 커튼 표면에 감춰져 있음을 커튼 주위의 우회로를 거쳐 비로소 마주하게 되는 것이다. 우리가 외면하고자 하나 엄연히 존재하는 불편한 역사적 진실은 평화롭고 안락한 현재적 장막의 일부로서 그것을 더 가치 있게 해주는 요소임에도 불구하고 그다지 큰 관심을 끌거나 의미를 부여받지 못한다. 드러남(아름다운 장식, 평안한 현재)과 감춤(학살의 끔찍한 이미지, 폭력과 억압으로 얼룩진 어두운 역사)이라는 상반되는 두 요소를 정교하게 직조하여 만든 이 커튼은 피상적 읽기로는 제대로 파악할 수 없는 역사에 대한 인식론적 태도를 성찰케 하는 장치로서 비본질적인 것이나 표면적 허상으로부터 일종의 관점의 전환을 제안하고 있다. 커튼 자체를 구성하는 불편한 이미지가 결코 간과해서는 안 될 역사의 실체적 진실임을 포착하면서 말이다.

우리가 몸담고 있는 세상을 떠받쳐주는 보편타당한(혹은 그렇다고 믿는) 지배적 논리에 대한 믿음을 부정하고 그에 대한 순응 또한 거부하는 신유라의 작업은 불온하다. 하지만 그 불온함으로 우리 내면에 굳건히 자리해 온 견고한 믿음과 배양된 사고에 균열이 일어나고 그것에 대응하는 반작용과 예민한 각성이 생겨남으로써 개인과 사회가 외면했던 실재, 우리 안에서 배척하고 추방하고자 했던 타자 등 현상의 본질과 실체적 진실에 다가서게 된다면 그것은 건전한 불온함이 아닐까?

글: 이정아