South Korea has the lowest birthrate in the world. According to the National Statistics Office, in the first half of 2022 the standard birthrate fell to 0.75, meaning that the average number of babies predicted to be born to each woman of childbearing age (15~49 years) was even less than 1. (The average birthrate for OECD countries is 1.65). The number of babies born in June 2022 in Korea was 18,830, a 12.4% reduction from the same month of the previous year. The issue of low birthrate has continued to reduce the population, and at the beginning of 2020, for the first time in its history, South Korea became a country with more deaths than births.

In 2021, 51% of Korean men in their 30s, and 34% of women, were unmarried (legally single). Compared with the unmarried rates of 2000, which were 19% of men and 8% of women, in the space of 20 years a trend has developed whereby young Koreans are not only not giving birth, but not getting married. Among the legally single, the percentage of those in their 20s and 30s who are not even in a romantic relationship is approximately 74%. Contemporary Korean youth say that romantic relationships, marriage, and children are unnecessary (National Statistics Office). The ‘three giving-up generation’ (those who avoid romantic relationships, marriage, and children) has transformed from renouncement to voluntary refusal.

Various factors have been pointed out as the cause of the low birth rate that is now a prominent social issue: social problems such as gaps in the labour market, intensifying educational competition, the price of real estate which prevents people from marrying and having children, and the intensification of the financial burden implied in the label ‘the first generation who are poorer than their parents’. Socio-economic issues and, after the pandemic, the rising of the ‘young and rich’ success myth radically led young people to investment crazes such as stocks, cryptocurrency, and NFTs. A deep sense of economic frustration worsened through conflict across lines of gender, generation, and social class.

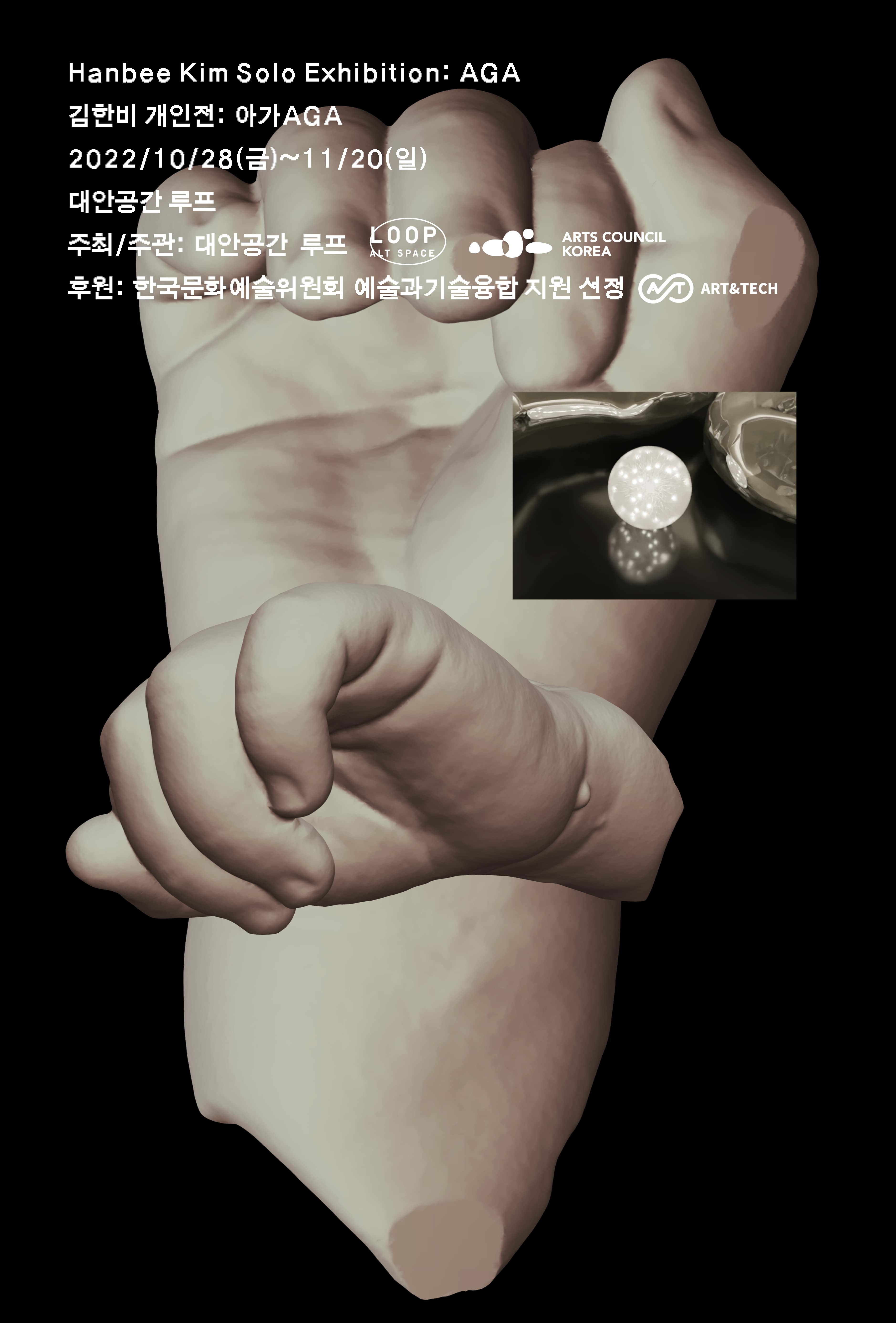

<Kim Hanbee’s exhibition: AGA> tells the story of the low birth rate issue through the gaze of a female artist in her 20s. Severe competition, comparison, uniform vision, learning by rote, transformation in consciousness of the existing trend that defines university-job-marriage-pregnancy-childbirth as standard or normal life, hostility towards traditional and rigid family norms, sense of relative deprivation produced by the ‘overnight beggars’ trope, all leads to a decline in the birthrate and population reduction. Not through social diagnosis or statistics but through emotional empathy embracing all generations, the artist attempts to address various reasons for the low-birth phenomenon such as these socio-economic issues and personal circumstances.

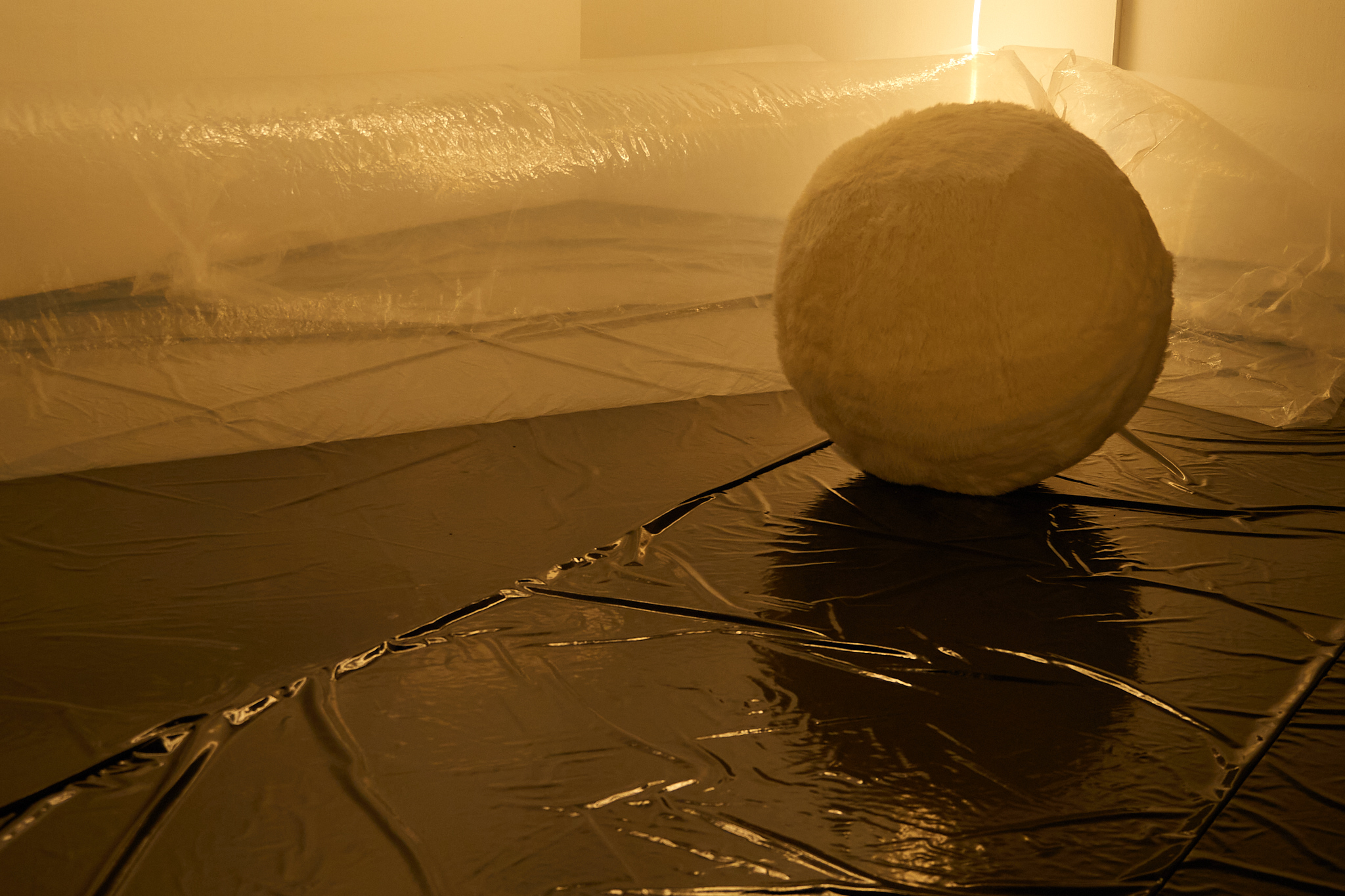

Kim Hanbee creates ‘AGA’ (which means a ‘baby’ in Korean), a robot companion that is unable to live without human beings’ acts of care. The human body, whose original meaning has faded due to the development of technologies and virtual worlds such as metaverses and online platforms, is given a new productivity through symbiosis with technology. Operating thanks to an energy harvesting and hall sensor, AGA is a parasite machine whose host is human energy. Wholly dependent on human movements, AGA implies the social perspective of the young generation.

The exhibition features as its chief work a participatory performance in which the gallery visitors move together in a seeming dance with ‘AGA’ inside an incubator installed by the artist. After putting on a magnetic wristlet, the visitors conduct a performance in which they themselves care for ‘AGA’. When the magnetic wristlet triggers ‘AGA’’s internal sensor, ‘AGA’’s central motor operates according to the sensor’s location. Through a servomotor ‘AGA’s balance shifts and a change of direction is achieved, and when ‘AGA’ moves voltage is generated through a piezoelectric element attached to the surface under ‘AGA’’s clothes. This voltage passes through the rectifier circuit and the battery recharges. In this way, a pesky or lovable ‘AGA’ who depends wholly upon human acts of care is completed. The visitors care for ‘AGA’, each making a narrative out of individual experience, varied bodies and environment.

Kim Hanbee, a heterosexual woman in her 20s, says that she cannot avoid questions about marriage and children. Someone earnestly wishes for it, someone else declares a preference for being single and childfree. Who is in the minority? The artist says that the phenomenon of worsening complaints and conflicts is an issue for all members of society, not only those in a special class. Through the performance of caring for ‘AGA’, the exhibition proposes recognizing everyone’s participation in contemporary issues as necessary work.

Text: Sun Mi Lee, Curator, Alternative Space Loop

Translated by Deborah Smith

Kim Hanbee (1996- )

Kim Hanbee majored in Painting at Ewha Womans University. She makes playgrounds based on spatial production, interaction and performance, with an interest in the meanings of the body which change according to technological developments. Her work begins in contemporary changes and cognitive consensus that can be felt in everyday life. And space, the body, and relationships change constantly within the work through the audience’s sensory experience and participation. Her central works include the solo exhibitions [Avatar-synchronization, Osisun & Theatrebase, 2021], and the group exhibitions [() trapped in (), Gallery Raon, 2020], [Rising tide and ebb tide, artspace+the necessaries, 2020].