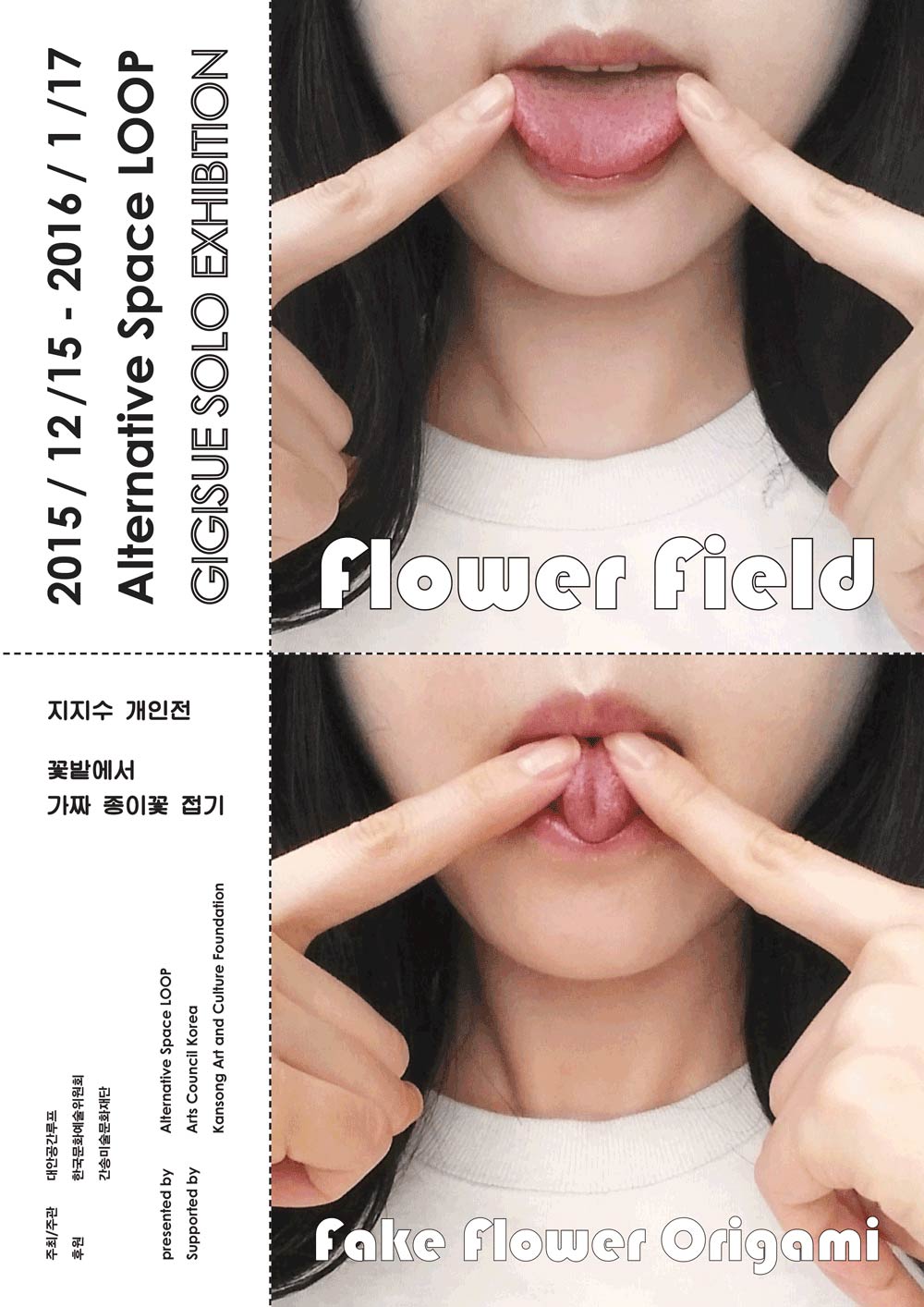

Gi Gi Sue Solo Exhibition: Flower Field Fake Flower Origami

- Venue: Alternative Space LOOP

- Organized by: Alternative Space LOOP

- Supported by: Arts Council Korea, Kansong Art and Culture Foundation

Gi Gi Sue Solo Exhibition: Flower Field Fake Flower Origami

- Venue: Alternative Space LOOP

- Organized by: Alternative Space LOOP

- Supported by: Arts Council Korea, Kansong Art and Culture Foundation

지지수 개인전: 꽃밭에서 가짜 종이꽃 접기

-장소: 대안공간 루프

-주최/주관: 대안공간 루프

-후원: 한국문화예술위원회, 간송미술문화재단

“In the flower field that I made with my father, the chrysanthemum is also in full bloom. / My dad broke the morning glory along with his band”. - In the flower field

The artist singly obsesses over the presence or absence of the father figure in her works. Why might this be? It is likely because of a special experience which has deeply impacted the artist’s life, but in fact not many things in our lives are probably as thoroughly bequeathed to us as our fathers’ names. Like a giant tree and roots allowing us to sustain our lives, and due to pivotal conditions and their central role in our individual lives; the name, father operates as the practical frameworks and foundation and, sometimes, as a barrier or shadow in society, including the artist. For this reason, the name of father is none other than the structure and institution, order and discipline, central symbolism and significance constituting actual society. This is designated the so-called patriarchy. Of course this possesses negative connotations. However, it deserves at least some attention since, like it or not, the name of father assumes certain weight in reality. The artist, too accepts this practical presence and authority of one’s father. Nay, she institutes paternal presence (as well as absence), which was of singly special significance, as the central axis of her work. Along with her private experiences, the artist, Gigisue is also presenting our society’s various internal conditions conferred upon those experiences; and, additionally, she is exposing the significance and operation of our era’s symbolic power, which operates under the name of one’s father.

The family’s significance transcends the individual’s private realm in today’s society. This is because the ironic aspects of our entirely complicated society are wholly projected and overlapped. It appears the presence of the artist’s family, particularly her father, was as such. Painful memories of the once-harmonious significance of the father figure deteriorating through replacement by capitalist economic logic and power games remained like old wounds. Because of extraordinary memories of having faced difficulties in life as an individual due to her father-daughter relationship, which should stay intimate, being transformed through our society’s dominant logic of money and power, and the complicated network of relatives related to this; the name, father is synonymous with our society’s central power system, i.e. patriarchical and phallocentric power, to the artist. Rather than simply limiting such private experiences to the level of personal experience, the artist uses a serial process of profoundly asking and ruminating over its significance through her work to reflect from alternative perspectives, heal and overcome. Therefore, the artist’s work was able to be not just an individuals’ personal story, but a story about all of our fathers, and about the society we set foot in, which continues to exist here. Particularly, the artist’s work commands very meaningful attention for possessing the direct post-capitalist codes of capital and desire. This is because one can confirm the presence of diverse tendencies and secret operations of power saturating our society and penetrating the microscopic realm of the individual’s life, in addition to the operation of macroscopic power and desire on society in general here. The artist uncovers the strange internal conditions and background implied by this secretive power network through her works, one by one, before presenting them with a long connection.

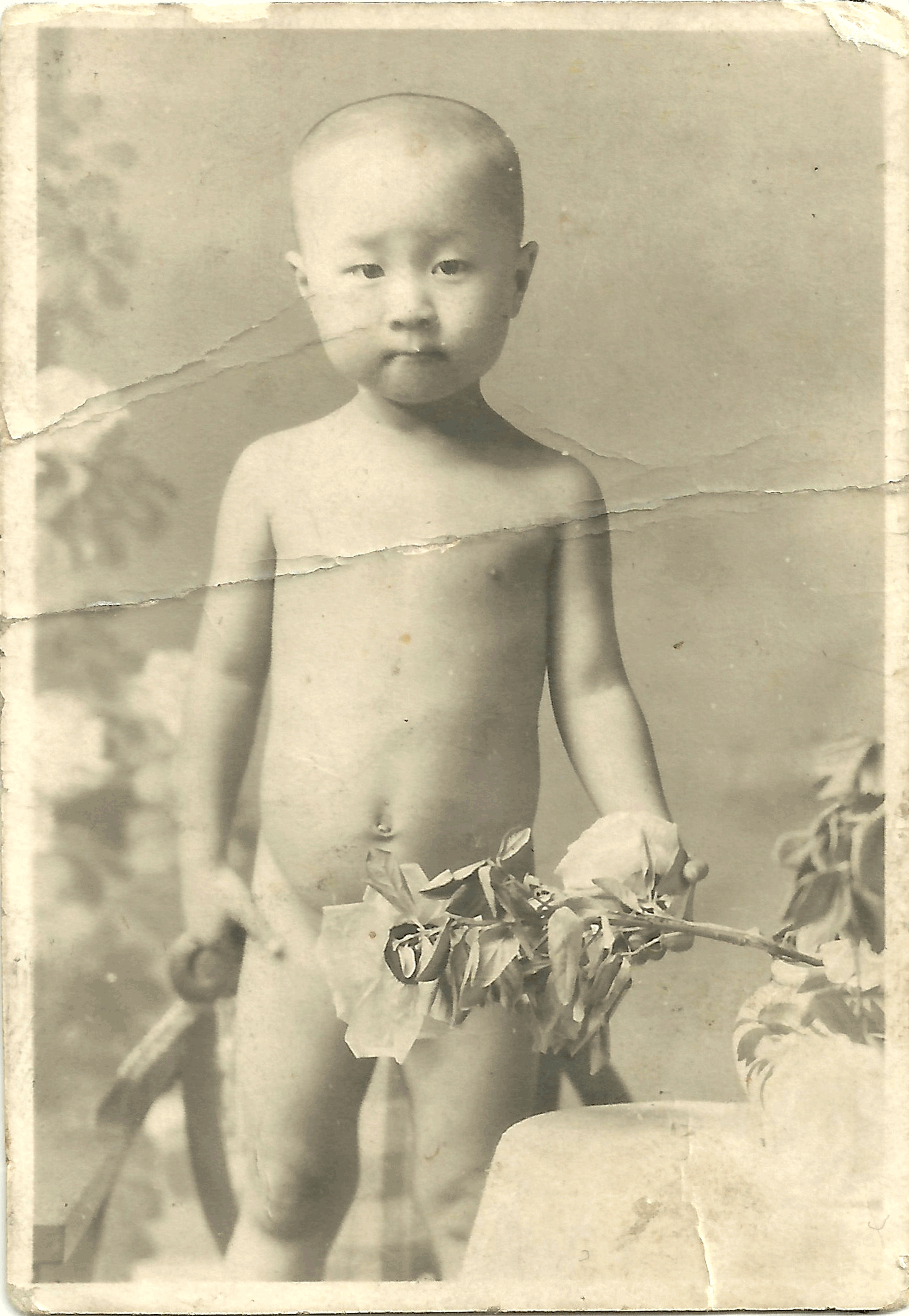

As much as the relationship is not simple, the image of the artist’s father represented by Gigisue is also variegated. Similar Figures, as the title suggests, reveals the artist’s relationship with her father in which the two are dissimilar but ultimately inevitably share mutual resemblances. It visually presents the artist’s father, who is embodied in slightly different images each moment like decals but ultimately certain to be Gigisue’s similar figure. Father Still Life expresses the absence and sense of presence of a father who now only exists as a fragment of memory but simultaneously also holds the place of eternal memory and longing through ironic beauty. Like that of still lifes, it strikes viewers as would a landscape illuminating us on as much as the meaning of our fleeting lives through that presence which feels like it is frozen forever. Transience and futility, as such, burst out revealing how Gigisue’s representation of her father is based on her longing. In this context, Fruits or Nuts works together with a faded photograph of Gigisue’s father from the artist’s childhood to reinforce this significance. The artist contradicts the significance of transience through an empty pepper object made of shroud gauze while simultaneously symbolizing wealth and power by hanging a gemstone on a tree branch with this photograph as a motif. Although these are likely works speaking of the futility and transience of power, they also appear to communicate the artist’s special feelings toward the old photograph, which happens to have been left to the artist by her father, to impart to viewers deep and earnest sentiments. One can also come into contact with the small, faded photograph which is its original form, to cut across the lengthy gap of space and time to face the artist’s secret yearning toward her father’s presence. The exhibition continues with this as its intermediation, and intensifies the artist’s critical thought or sensibilities as it expands its denotation into video and installation work.

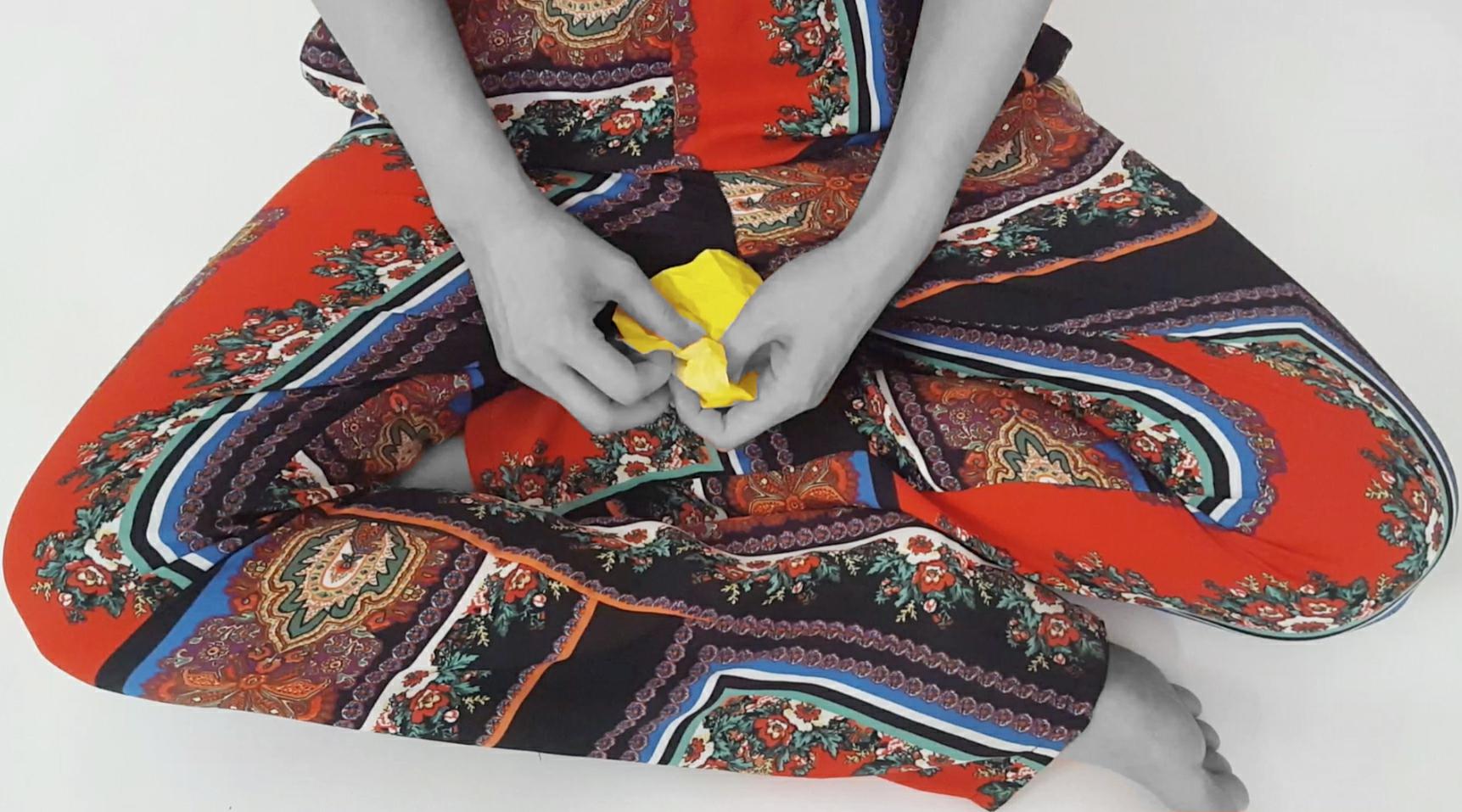

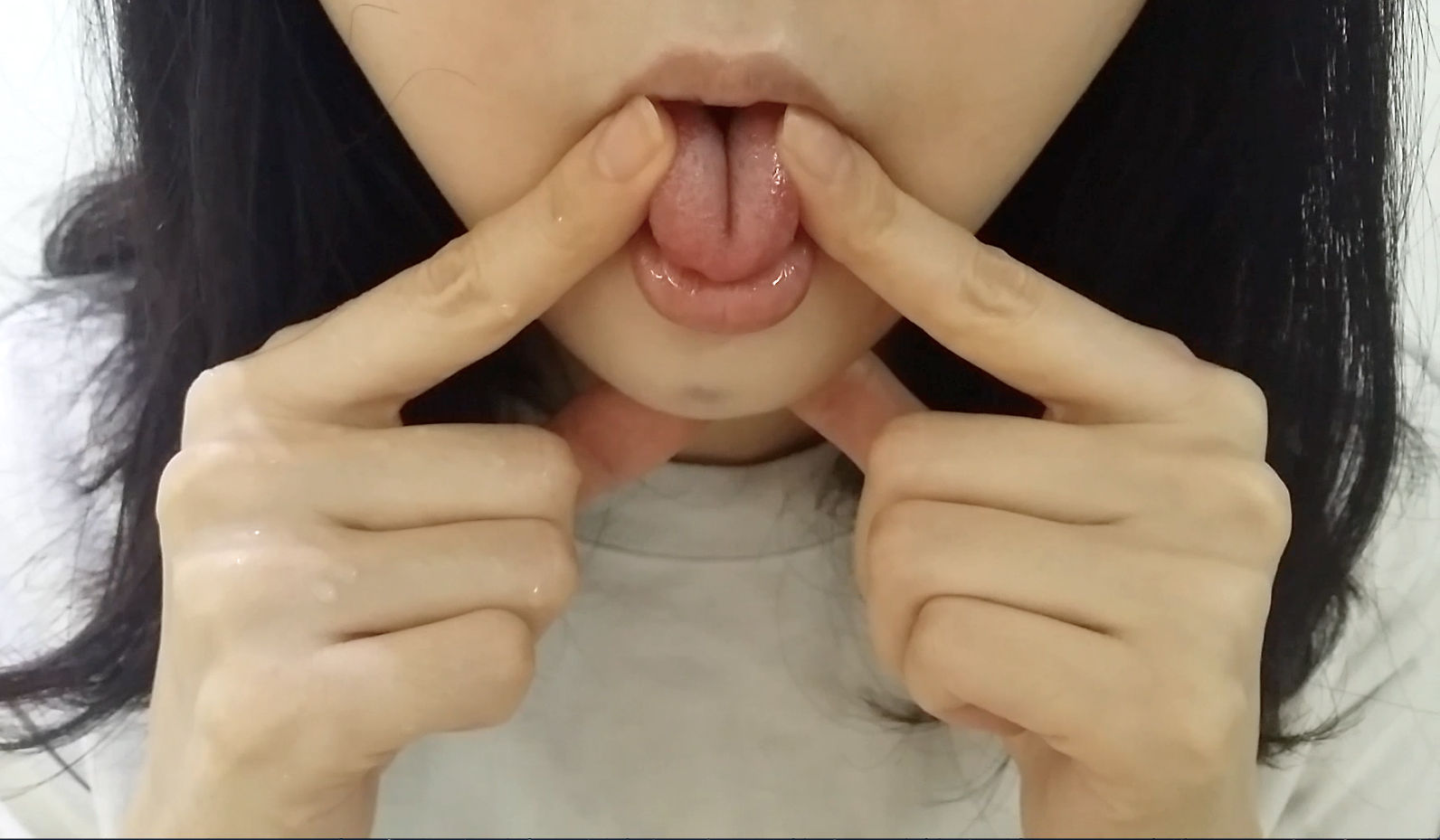

An image of lotus-position, or Indian-style, sitting, which is traditionally how men would sit in Korea, Patriarch Seating Position doubly satirizes how even postures and attitudes are regulated and, at the same time, idealized and treated as absolute in our male-dominated society; and it shares the same context or extended plane with the ensuing serial pieces of Missing One and Biddy, demonstrating the artist’s act of searching for male genitalia which has gone missing from her body and speaks of (the sadness of) female silence- enforced by a traditional patriarchical taboo- through Gigisue’s act of torturing her own tongue, respectively. The artist expresses her father’s presence and its genial relationships using her physical actions and performance through this series of works. Particularly, these three works draw attention in how they are all based on the artist’s body, and these pieces, in which the artist presents parts of her body through minimal, restrained and repeated actions, demonstrate how even Gigisue’s body is deeply connected to patriarchical and phallocentric power. Such aspects are, in particular, symbolically revealed in Missing One, and this is because the artist repeats the ironic act of looking for male genitalia on herself, which are not there (physically), but still operates as a different power of social significances. The significances Gigisue ultimately seeks to find is ultimately something which does not exist in reality, as such, but at the same time subsists as paradoxical senses impressed onto the artist’s body. Such paradoxical senses are also visible in Wombmorphia; and this piece, which expresses the artist’s Jonah complex resulting from her losing her father, i.e. a longing directed at the womb of the artist’s mother, makes clear that what the artist seeks is ultimately something which is paradoxically already lost but nonetheless a goal the artist must forever essay to reach. They are objects one may pursue but cannot reach, things which are ceaselessly approached to then just slip back away. In this way, significances endlessly drift without becoming anchored in a fixed state. The artist, too irrepressibly makes visible those close yet ironic sensorial masses through such ceaseless actions known as one’s father.

Direct relations between paternal presences and contemporary capitalism is confirmed in The Realm. The artist had to experience a legal inheritance dispute after her father’s death, and in this process she suffered mental shock and pain, and confusion while watching the significance of family become reduced to economic logic surrounding capital. Love between a father and his daughter, and family intimacy was replaced by the logic of capital, and our society’s current desire for capital set in. As such, the artist’s work expands to encompass the more inclusive and original significances implied by the appellation of father. Toward the giant social power of one’s father, which operates microscopic influences over the individual’s private relationships, and the authority of its meaning, that is. However, Gigisue’s work still appears to be more far reaching than being limited to contexts of social significances. This is because a certain sense of anxiety is deeply situated here. We can perhaps glimpse, if vaguely, into the artist’s such emotions in Drain 123: self-portrait. Even tall piles of snow melt and disappear into drain holes, but a small tree stands in the middle of a snow-covered piece of land. Blurry tears are pooled at the edges of half-closed eyes in the following image. All of these pieces are subtitled self-portrait. Although the artist attempted to sing of the false appearance of our patriarchical society through the denomination of fathers, perhaps paternal presence to the artist was still this clear and intact, purely profound reality which could not erased if one strove to do so. Just like how all of our fathers’ places are as such.

Min Byung Jic, Vice Director, Alternative Space LOOP

아빠하고 나하고 만든 꽃밭에 채송화도 봉숭아도 한창입니다. 아빠가 매어놓은 새끼줄 따라 나팔꽃도 어울리게 피었습니다.

_꽃밭에서

어린 시절 즐겨했던 이 동요 속에 이번 전시의 의미심장한 의미들이 녹아있다. 가사 그대로는 아니다. 아빠와 함께 했던 어떤, 행위들, 그 추억들이 긴 여운으로 자리하는 것이다. 그렇게 아빠와 작가, 그리고 과거의 어떤 기억들이 주어와 동사로 흔적처럼 남아있지만 핵심적인 목적어, 곧 어떤 사건들이 듬성듬성 빠져 있어, 영원히 돌이킬 수 없는 과거의 시간, 공간으로 남는다. 이 사건들은 작가가 기억하고 추억하는 것들이지만, 지금은 없는 것들이기에 그 부재한 빈자리를 다른 의미들로 채워놓으면서, 다른 방식들로 반추한다. 작가 작업의 기본적인 얼개들이다. 이를테면, 꽃들이 없는 꽃밭인 셈인데, 전시의 타이틀이기도 한 동명의 비디오 영상작업에서 작가는 아버지의 고향 인 제주도의 꽃밭과 자본주의 상징인 맨해탄 증권가 빌딩 숲 이미지를 교차시키면서 가짜 종이꽃을 접는다. 지금은 부재하는 아버지와의 단란했던 기억을 가짜 종이꽃 접기로 대신하고, 이러한 아버지의 존재가 비단 개인적인 경험만이 아니라 현대 자본주의 가부장제와 연결되었음을 부각시키고 있는 것이다. 지금은 부재하는 어떤 추억에 대한 그리움인 동시에 친근해야 할 부녀간조차 거짓되고 어긋난 사회적 관계들로 변모할 수 없는 상황에 대한 암시이자 이번 전시 전체를 관통하는 작가의 화두인 셈이다.

이번 전시를 포함하여, 작가는 유독 작업에서 아버지라는 존재 혹은 부재에 집착한다. 왜였을까? 작가의 삶에 깊은 각인을 남겼던 특정한 경험 때문이기도 하겠지만, 사실 우리의 삶에서 아버지의 이름만큼이나 삶에 짙게 드리운 것도 없을 것이다. 삶을 지탱하게 하는 거대한 나무이자 뿌리처럼, 그리고 개인의 삶을 좌우 할 만큼의 중요한 삶의 조건들이자 그 중심적인 역할들로 인해 아버지라는 이름은 자신을 포함하여 사회의 현실적인 뼈대이자 지반으로, 때로는 장벽이자 그림자로 작동한다. 이런 이유로 아버지라는 이름은 현실 사회를 이루는 구조이자 제도, 규율과 훈육, 중심적인 상징과 의미에 다름 아니기도 하다. 이를 지칭하는 것이, 이른바 가부장제이다. 물론 좋은 의미는 아니다. 하지만 좋든 싫든 아버지라는 이름은 현실의 어떤 무게로 자리하기에 쉽게 외면할 수도 없는 노릇이다. 작가 역시도 이런 아버지의 현실적인 존재, 그 무게감을 받아들인다. 아니 유독 남다른 의미로 자리했었던 아버지의 존재(그리고 부재)를 작업의 중심축으로 설정한다. 단지 어떤 개인적인 경험만이 아니라 그 내밀한 경험 속에 드리운 이 사회의 다양한 속내들을 펼쳐내고, 이에 더해 아버지의 이름으로 작동하는 이 시대의 상징적 권력의 의미와 작동을 드러내고 있는 것이다. 개인의 내밀한 경험만큼이나 절실하게 이 사회의 어떤 단면들을 드러낼 수 있는 대상도 없었기 때문인 듯싶다. 그렇기에 단지 가족으로서의 어떤 그리움만은 아니었던 것 같다. 이에 머물지 않고 아버지라는 한없이 크고 무거운 존재를 통해 세상이 숨겨놓은 그 이면의 것들조차 가시화시키려 하니 말이다.

가족의 의미는 대게는 안락하고 평온한 것들일 테지만 현실의 가족이 항상 그런 것만은 아니다. 어쩌면 그 평온함 속에 자리하는 이질적이고 모순적인 것들로 인해 우리는 가족의 애틋한 의미, 소중한 의미를 더했는지도 모르겠다. 특히나 현대사회에서 가족의 의미는 개인의 사적인 영역을 넘어선다. 곧 복잡하기만 한 이 사회의 모순적인 것들이 그대로 투영되고, 겹쳐지기 때문이다. 작가에게 있어 가족, 특히 아버지의 존재가 그러했던 것 같다. 단란했던 아버지의 의미가 이 시대, 자본주의의 경제 논리와 권력 게임으로 대치되면서 변질되었던 아픈 기억들이 오랜 상처처럼 남아 있었던 것이다. 친밀해야 할 부녀간의 관계가 이 사회의 지배적인 권력, 환금의 논리로 변모되고, 이에 얽힌 가족, 친족 사회의 복잡한 그물망으로 인해 힘겨운 개인의 삶을 살아야 했던 각별한 기억들로 인해, 작가에게 있어 아버지의 이름은 이 사회의 중심적인 권력 시스템, 곧 가부장적이고 남근중심적인 권력에 다름 아니게 된다. 어쩌면 이러한 아픈 기억들은 어떤 형태로든 개인의 평생의 삶에 그림자로 길게 드리웠을 수도 있었을 것이다. 하지만 여전히 그 기억들은 이어지겠지만 작가는 이러한 내밀한 경험을 단지 개인적인 경험의 차원으로 한정시키지 않고, 작업을 통해 곰곰이 그 의미를 되묻고, 되새김질하는 일련의 과정을 통해, 다른 시각으로 반성하면서, 치유하고 극복해간다. 아니, 이러한 경험을 통해 이 사회가 드리운, 친밀성의 정치학을 가시화시킨다. 그렇기에 작가의 작업은 비단 개인의 이야기만이 아니라 우리 모두의 아버지에 관한 이야기, 지금, 여기 계속해서 자리하고 있는 우리가 내딛고 있는 사회에 관한 이야기일 수 있었던 것이다. 특히나 작가의 작업은 자본과 욕망이라는 후기 자본주의의 직접적인 코드를 갖고 있어 의미심장한 관심을 요한다. 이를 명시적으로 드러내는 직접적인 작가의 화법도 독특한 느낌을 준다. 사회 일반에 관한 거시적인 권력과 욕망의 작동만이 아니라 개인의 미시적인 삶의 영역을 관통하고 있는, 이 사회에 가득한 권력의 다양한 흐름과 그 내밀한 작동마저 확인할 수 있기 때문이다. 그 비밀스러운 권력의 그물망이 함의 하는 기묘한 속내와 이면을 작가는 작업을 통해 하나하나 파헤치고, 긴 맥락으로 펼쳐낸다. 이번 전시가 말하고 있는 것들의 근본적인 얼개들이다.

간단치 않은 관계인만큼, 작가가 그려내는 아버지의 이미지 역시 다채롭다. 이를 전시의 동선을 따라 살펴볼 수 있도록 하자. 처음 만나게 되는‹닮은꼴Similar figures›은 그 제목만큼이나 닮지 않은, 그러나 결국은 닮을 수밖에 없는 아버지와 작가의 관계를 드러낸다. 마치 데칼코마니처럼 매순간 조금은 다른 이미지로 형상화되지만 결국은 닮은꼴일수 밖에 없는 아버지라는 존재를 가시화시키고 있는 것이다. 지우려 해도 지울 수 없는 흔적처럼,작품 속의 애써 가꾸고 피워낸 꽃을 담은 이미지가 남다른 느낌을 전한다.‹아버지 정물화Father still life›는 이제는 기억의 단편으로만 자리하는, 하지만 동시에 영원한 기억과 그리움으로 자리하는 아버지의 부재와 존재감을 역설적인 아름다움으로 표현하고 있는 작품이다. 단란했던 애틋한 추억으로 인해 당신의 존재가 화려한 아름다움의 의미로 기억되지만, 지금, 여기 부재하는 아버지는 삶의 한시적 순간과 영원성을 동시에 느끼게 하는 존재일 것이다. 마치 정물화의 그것처럼, 영원히 정지된 것만 같은 그 존재감으로 덧없는 인생의 의미마저 일깨우는 그런 풍경처럼 말이다. 우리 모두는 이처럼 언젠가는 부모의 존재를 부재로 영원히 마음속에 담아두어야 하는 그러한 삶을 살아가야만 한다. 어릴 적 아버지와 함께 그렸던 낙서들을 형상화시킨 이미지가 작가의 애틋한 마음마저 담고 있는 것 같아 긴 여운을 남긴다. 이처럼 덧없음과 허무함은 작가가 그리고 있는 아버지의 이미지가 결국은 그리움에 바탕을 둔 것임을 못내 드러낸다. 이런 맥락에서‹과일 혹은 열매Fruits or Nuts›는 어린 시절 아버지의 모습을 담고 있는 빛바랜 한 장의 이미지와 연동되면서 이러한 의미를 배가시킨다. 작가는 이 사진을 모티브로 하여 나뭇가지에 원석을 매달아 부와 권력을 상징하는 동시에, 수의용 거즈로 만든 텅 빈 고추 오브제를 통해 덧없음의 의미를 상충시킨다. 권력의 허무함과 무상함을 말하는 작업이겠지만 아버지의 유품이기도 할 낡은 사진 이미지에 대한 작가의 각별한 마음마저 전하는 것 같아 애틋한 느낌도 함께 전해진다. 그리고 그 원형이 되는 빛바랜 작은 사진 또한 접할 수 있어 그 긴 시공간의 간극을 가로질러 아버지의 존재를 향한 작가의 내밀한 그리움으로 향하게 한다. 전시는 이를 매개로 다시 이어지는데, 영상, 설치 작업으로 외연을 확장하면서 작가의 문제의식 혹은 그 감각의 강도를 확장시킨다.

남성의 앉는 자세인 가부좌를 이미지화시키고 있는‹아빠다리(가부좌)Patriarch seating position›는 남성중심 사회에서 자세와 태도마저 규율화 되고, 동시에 이상화되고 절대시되고 있음을 이중으로 비트는 작업인데, 이어지는 일련의 작품들인 자신의 몸에서 사라진 남성의 성기를 찾는 행위를 보여주는 ‹Missing One›, 자신의 혀를 자학함으로써 전통 가부장제 속에 규율금기로 자리하는 여성의 침묵(의 슬픔)을 말하는 ‹Biddy›와 같은 맥락 혹은 연장선상에 있는 작업이다. 이들 일련의 작업을 통해 작가는 아버지의 존재, 그 살가운 관계들을 작가의 신체적인 행위, 퍼포먼스로 연동시킨다. 특히나 이 세 작업 모두 작가 자신의 신체를 기반으로 한 작업이라는 면에서 눈길을 끄는데, 자신의 신체 부위를 최소한의 절제되고 반복된 행위로 보여주는 이들 작업은 자신의 육체마저도 가부장적인 남근 권력과 깊숙이 결부된 것임을 보여준다. 물론 단순한 반복의 형태는 아니고 이에 대한 모순적이고 혼란스러운 감정들과 함께 하면서 말이다. 이는 이러한 행위들의 재연이 남성 중심의 신체화 된 권력, 곧 태도, 자세 등의 몸가짐에까지 작동하는 미시적인 훈육권력의 차원을 드러내는 것이기도 하겠지만 아버지라는 몸뚱이를 빌어 존재하고 있는 또 하나의 내 안의 또 다른 신체성을 확인하는 의미 또한, 가지기 때문일 것이다. 이러한 면모들은 특히 ‹Missing One›에서 상징적으로 드러나는데, 자신에게 (신체적으로) 부재하지만, 다른 사회적 의미 권력으로 여전히 작동하는 남근을 찾는, 모순적인 행위를 되풀이 하고 있기 때문이다. 그리고 작품 속 허름한 아버지의 내복은 작가에게 거추장스럽고 불편하지만, 그럼에도 현재의 자신의 이미지를 형성하고 있는 대상을 드러낸다. 이들 이미지가 사회적 존재의 표지처럼 작동하고 있는 것이다. 결국 작가가 찾고자 하는 그 의미는 이처럼 현실적으로 존재하지 않는 것이면서도 동시에 신체에 각인된 모순적인 감각들로 자리하는 것들이다. 이러한 모순적인 감각들은‹자궁중독 Wombmorphia›작업에서도 볼 수 있는데, 아버지의 상실로 인한 요나 콤플렉스, 곧 어머니의 자궁을 향한 그리움을 표현한 이 작업은 결국 작가가 추구하는 것이 이미 잃어버린, 하지만 그럼에도 불구하고 영원히 도달되어야 할 역설적인 것임을 분명히 한다. 닿으려 해도 닿지 않는 대상들, 끊임없이 접근되지만 다시 미끄러지고 마는 그런 대상들인 것이다. 의미는 이처럼 고정된 채로 정박되지 않고 끊임없이 표류한다. 하지만 애초에 의미란 그런 것들이 아니었을까. 세상의 모든 의미들은 이처럼 정해지고 고정된 방식이 아니라 유동하는 흐름 속에 자리하면서 이에 대한 부단한 접근 속에서 어렴풋하게 그 모습을 드러내는 것들 일 테니 말이다. 작가 역시 이러한 끊임없는 행위들을 통해, 아버지라는 저 가깝고도 모순적인 감각의 덩어리들을 못내 가시화시킨다.

아버지라는 존재와 동시대 자본주의와의 직접적인 관련성은 ‹제국The Realm›에서 확인된다. 아버지 사후 법적인 재산 분쟁을 겪어야 했던 작가는 이 과정 속에서 가족의 의미가 자본을 둘러싼 경제논리로 환원되는 것을 지켜보면서, 정신적인 충격과 고통, 혼돈을 경험해야 했다. 부녀간의 사랑이, 가족 간의 친밀성이 자본의 논리로 대체되고, 그 자리에 지금 이 사회의 자본을 향한 욕망이 자리하게 된 것이다. 작가의 작업은 이처럼 아버지라는 이름이 함의하는 더 포괄적이고 본원적인 의미들까지 확장한다. 개인의 내밀한 관계에 미시적인 영향력을 작동시키는 아버지라는 저 거대한 사회적 권력, 그 의미의 무게감을 향해 말이다. 어쩌면 이를 확인할 수 있는 작업이었기에 작가의 작업이 단지 아버지에 대한 개인적인 집착이 아니라 더 넓은 공감의 차원을 획득할 수 있지 않았나 싶다. 여전히 이 시대는 저 아버지라는 무겁고 큰 존재의 그물망, 그리고 그 그물망이 엮어놓은 가부장적이고 남근중심적인 상징권력, 그리고 자본마저 착종된 모순적인 억압의 구조 속에서 작동되고 있기 때문이다.

하지만 작가의 작업은 그럼에도 불구하고 사회적 의미의 맥락으로만 한정되지 않는 것 같다. 어떤 애틋한 그리움 같은 것들이 짙게 자리하기 때문이다. 그 부재함을 향한 희구의 몸짓이 느껴지는 것이다. 그렇기에 작가는 그 부재함을 다른 식의 존재감으로, 현재의 살아있는 의미의 지속적인 현현으로 그렇게 계속해서 반추했던 것이 아니었나 싶다. 아니 자신의 현재적 삶에 여전히 무게를 드리우고 있는 아버지를 향한 양가적인 심정들로 인해 부단히 힘들어했던 것은 아니었을까. ‹배수구 123Drain 123: self-portrait›에서 작가의 이런 심정을 흐릿하게나마 엿볼 수 있지 않나 싶다. 소복이 쌓인 눈들조차 배수구로 녹아 없어져 버리지만 그 눈 밭 사이에 작은 나무 한 그루가 덩그러니 자리하고 있다. 그리고 이어지는 이미지에는 반쯤 감긴 눈가에 흐릿한 눈물이 고여 있다. 모두 자화상이라는 부제가 달려있는 작업들이다. 아버지라는 이름을 통해 가부장적인 이 사회의 거짓된 모습을 노래하고자 했지만, 작가에게 아버지라는 존재는 여전히 애써 지우려 해도 지울 수 없는 그런 선연하고 오롯한 그런, 깊기만 했던 존재가 아니었나 싶은 것이다. 우리 모두의 아버지들이 그렇게 자리하는 것처럼 말이다.

글: 민병직