Five years have already passed since 2:46, March 11th, 2011- the Great Earthquake of East Japan. We surely must remember more than simply the enormous natural calamity our neighboring nation of Japan suffered, or the accident at a nuclear reactor resulting in massive radiation leakage. It is because this was a painful event which could only be explained as an atypical natural, or human-made, disaster aided or caused by people’s inability to control and manage natural events; and the event allowed us to seek anew humanity’s lives, which must coexist with nature, and thus ultimately reflect on inherent human life itself. Outweighing those deep wounds disasters inflict on us in importance is how these events cause us to look back and reflect on ourselves. Just as it is in all other areas of human life, contemporary arts and culture, too are likely incapable of being completely free from such scars and memories of cataclysms.

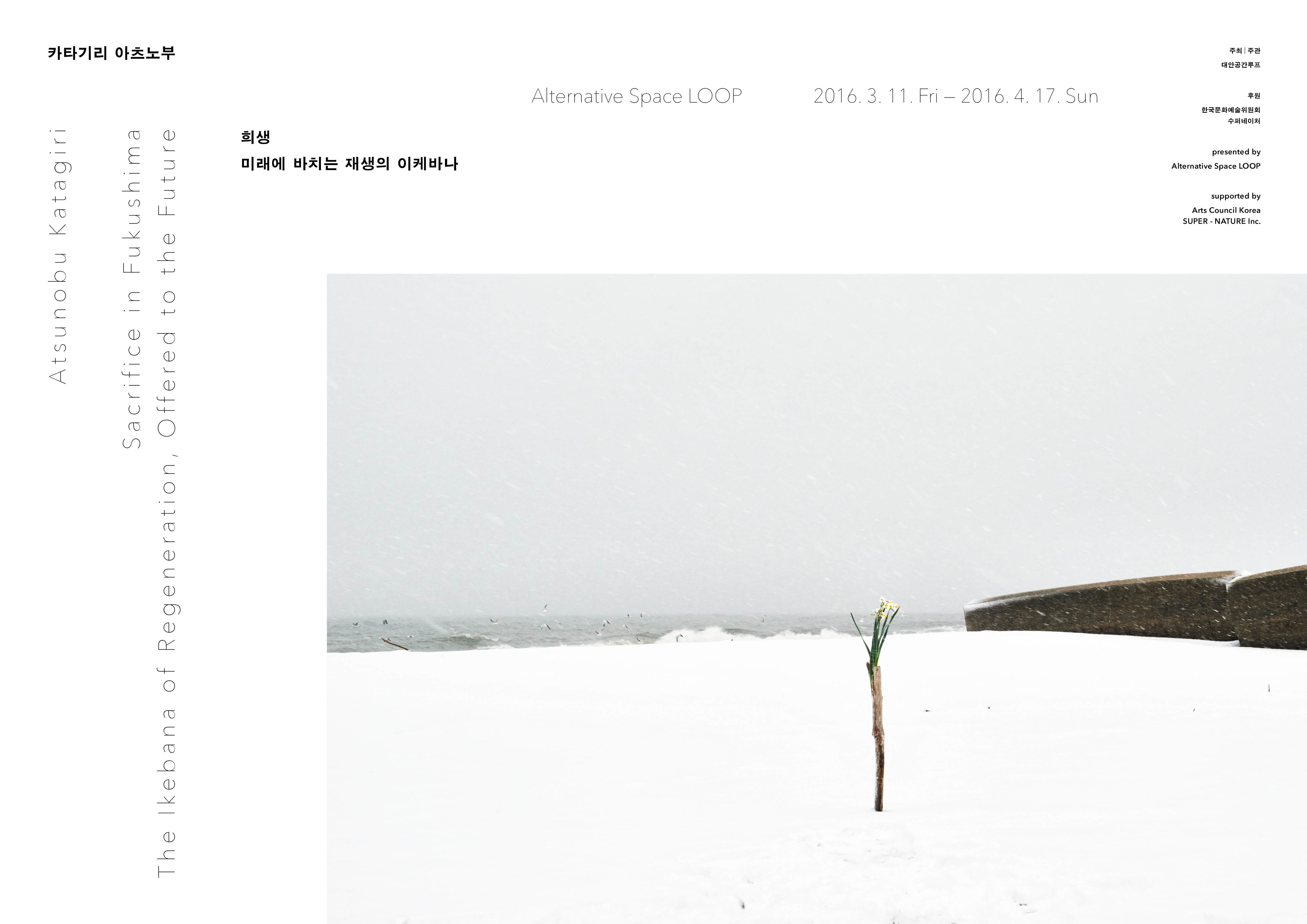

The works of ikebana (生(け)花), or traditional Japanese floral arrangement, initiate Atsunobu Katagiri in the current exhibition, too are positioned in such a context. Katagiri began visiting the town of Minamisoma in Fukushima Prefecture, located within a twenty-to-thirty-kilometer radius from the accident site in what is known as kenai (圈內, the zone), since mid-September of 2013, about two years after the disaster; moved there on December 28th of the same year and lived there through July 31st of the following year, of 2014. Just as how the significance of ikebana is to make flowers (花,はな) “come alive (生ける/活ける, いける),” the artist renewed his life at that extreme site, comparable to a desolate end of one’s life, through flowers. The artist thus witnessed the most difficulty-filled landscapes of life tenuously continuing its existence even amidst the devastation following the above disaster, and worked with innumerable flowers which arduously blossomed there while photographing this. He likely lived at the fringes of a calamity, but may also have been living while witnessing another landscape of life bordering death. This exhibition, as such, wholly delivers the artist’s reflections regarding the humanity and nature he faced during this time in his life.

Flowers blossom everywhere in the world, everywhere where life exists. Actually, flowers even blossom at the borders of death adjacent to life. Flowers are aspirations and gestures toward life. As an artist of flowering plants in Fukushima Prefecture, which a certain tragedy has made to resemble a pile of ash, Katagiri realizes anew such simple and self-evident significances of flowers. Like ikebana is an act allowing flowers to live, the artist transcends just plain ikebana- of allowing flowers to live in beauty in vases- to practice a floral arrangement facing a weakened world. The artist has set out in search of flowers extending their life amain, even amidst such a colossal natural and human-made disaster, while touring a devastated land, meditating on it while feeling it with all his senses. Therefore, the flowers the artist has sought after likely belong to more than Mother Nature. They were likely messages of hope regarding the many souls who were sacrificed in the calamity, or the presence or lives of the remaining, who have courageously continued living despite difficult life circumstances. While practicing a floral arrangement for all of them, the artist has lived another life of hope with the others who still remain at a site where many have left. This is why the artist’s current project is, like a sort of ceremony, a performance transcending the simple act of floral arrangement, and analogous to practicing life for all of us. Practicing directed toward people who remain hopeful amidst destroyed homes, and those grand currents of Mother Nature becoming renewed through alternative regeneration and rehabilitation even within the extreme disaster of nuclear pollution, as well as those who have fallen victim to the aforementioned tragedy, that is. Perhaps the artist was attempting to personally experience a life of self-discipline in which his own life could be newly purified and renewed through this. Katagiri has thus delivered a sympathetic perspective toward the existences of all who suffered due to the Great Earthquake of East Japan, and practiced floral arrangement work sympathizing and communicating with Nature’s principles while listening to the victims’ diminished voices. This is how the debris of lives destroyed by the tragedy could become found-objects and all of the nature at the disaster sites was able to become floral arrangement elements. Ikebana, to Katagiri, is now the business of fully growing hopes of life regarding the future, which refuse to cease even in the face of adversity, as well as the voices of life now lost; and simultaneously reveals the artist’s emotions and will regarding this while it transitions to an act of externalizing as flowers the artist’s certain, deep reflections regarding the world. It thus becomes a sacred act of connecting to life the gestures leading one to hope again amidst ruins, and even death. I.e., it becomes sacrifice.

The Ikebana of Regeneration, Offered to the Future.

Sacrifices signify live offerings to a divine being. A sacrifice is not an ordinary death. It allows life. Floral arrangement, which takes its place in the form of a ceremony, too holds the significance of a sacrifice, and so withered flowers may not be offered as sacrificial offerings. Only freshly picked flowers may perform the role of being sacrificed. They thus allow for the extension of life through live deaths. Sacrifice, which thus mysteriously connects life with death, holds a place facing future hope as present, as opposed to past, life. This circumstance has led to the exhibition being subtitled, “The Ikebana of Regeneration, Offered to the Future.” Above all, also, the lives of all these which blossom again through delicate gestures, even at a burdensome disaster site to cause the barren land to grow again and sustain itself, likely represents the very essence of sacrifice. Sacrifice is thus sustained toward the future, which is synonymous with new life. Additionally, it allows connections to past lives continuing toward the future. Fukushima Prefecture is where an abundance of artifacts from Japan’s prehistoric period of the Jomon Era (繩文時代) have been discovered, and the artist also attempts grafting his work to past lives, of when flowers in ancient Japan must have been planting their roots, through ikebana work using the Minamisoma City Museum’s artifacts. Katagiri has reconnected present lives facing the future to past lives. As such, the principles of Nature face the future while holding onto the present’s connections to the past. In this regard, ikebana is more than simply aesthetic floral arrangement. It can simultaneously be both an act connecting present lives to the past and a special action reconnecting present lives to future ones. This is because the very existence of flowers planting their roots into the earth connects with the past, and they continue their present lives into the future while repeating their life. However, flowers are hardly alone in connecting the joints of time together, as everything placed in our world for the purpose of life likely continue death and life while thus blossoming and withering again. Through his work, the artist realizes how ceaseless life and death are being repeated under the earth flowers are rooted in, and reconfirms how floral arrangement work can be something which thus connects life with death, in other words a life reborn from death.

It was for such reasons that floral offerings have found their place in religious ceremonies and various aspects of daily culture since ancient times in both the East and the West. Relative to human beings’ limited life-spans, flowers are given new life at their last living moments facing death. It is because they blossom again as eternal beauty at the moment of death and life. They possess renewability. For this reason, flowers signify and symbolize renewal and revitalization. In addition to these general significances of flowers, the artist makes flowers’ significances of revival and recovery even clearer by dramatically contrasting them with humanity’s catastrophic ways. Those clear and elaborate colors which only seem to fully emit their presence even at an ashen disaster site, and the graceful figures facing life even in moments of death, reflect this. Thus, this exhibition’s flower images and video capture the distinct attitudes toward life held by the people who, through their frail but solid gestures, have never lost their hope for the future despite their reality of a confused and miserable disaster. Those sorrowful yet infinitely beautiful appearances are likely their lives themselves which have been delivered to us, and simultaneously none other than a message and gestures of a certain hope which allows us to continue living again. Together with this, they give form to certain future values, in which people and nature must coexist without borders between them. It is because flowers have bloomed at those borders, within the division, and will blossom again.

Also, a performance by the dancer, Lee Mi-hee, who worked with the artist at the disaster site, moves all of us through sublime gestures seeking to oust evil energies and misfortune while firmly getting back on one’s feet with new hope, if on barren soil. This, too must be one and the same as an act of flowering. Such a desire and will for restoration and revival are reconfirmed in this exhibition’s floral installation piece using suspension and paper boats. Particularly, this piece resonates more extraordinarily and profoundly with us Koreans, who have experienced the disastrous tragedy of the Sewol Ferry and are still bound to an extent by the resulting wounds and pain.

As such, this exhibition visualizes a reflective image of salvation regarding an enormous catastrophe comparable to humanity’s Original Sin. However, rather than stopping at reminding us of the social and cultural significances of the Great Earthquake of East Japan’s calamity and disaster itself, which are still in progress; it delivers a certain hope of all of us, which humanity cannot help but have, through the ceremonial and artistic act of floral arrangement, which is likely none other than a gesture of hope even amidst such miserable ruins. It also leads us to reflect once again on contemporary art’s significance, role and attitudes regarding the realm of disasters by pulling that realm into the magnetic field of today’s art culture. It also has us confirming how even the exceedingly aesthetic, ordinary act of arranging flowers for appreciation can only achieve the rich significances of contemporary arts when it is based in reality and directed at all of our futures. We thus share and sympathize with how modest and ordinary practices firmly rooted in the soil of reality can gain new life as contemporary art to become life’s major topic of hope.

Written by Min Byung Jic

Vice Director, Alternative Space LOOP

Atsunobu Katagiri

Born 1973 in Osaka,Japan. At the age of 24, he became the head master of Misasasgi Ikebana school. Known for incorporating both traditional and modern approaches in his Ikebana works, as well as for collaborating with artists of different mediums. Katagiri`s work ranges from small scale compositions using wild flowers to large compositions using the cherry blossom, a theme he has maintained for several years. Through his works, he contemplates the concept of “Anima“-the primary motif of Ikebana-and through the use of flowers he creates a unique aura.